The Selkirk Settlement 1811-1821:

Maureen Matthews D. Phil. (Oxon)

Curator of Cultural Anthropology

The Manitoba Museum

When Lord Selkirk initiated an agricultural colony at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, he was responding to a world in transition. Liberalism and industrialization challenged existing world views; the rise of the American and French republics challenged existing orthodoxy. The Napoleonic wars raged, although in North America the British had earlier conquered New France, or Quebec. The American settlement frontier moved west, at great cost to indigenous societies. In Rupert’s Land, emerging Montreal-based fur trade companies, such as the North West Company, challenged the dominance of the long-established Hudson’s Bay Company. First Nations, responding to new economic opportunities, as well as the pressures of high mortality from imported diseases and settler encroachment, adapted to their changing environment.

The arrival of the Selkirk settlers in the Red River region in 1812 presents a microcosm of these global forces. First, the dislocation of the settlers themselves, as traditional social relations in the Scottish Highlands broke down. When aristocratic landowners found sheep to be more profitable than tenant farmers, the resulting Highland clearances provided a “push” for emigration. The Earl of Selkirk, a Scottish nobleman with wealth and a strong social conscience, facilitated the relocation of some of these victims of the clearances to British North America.

The area around the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers was already important in the fur trade, both as a transportation route and as a centre of provision supply. By 1805 the competition between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company was heated, sometimes leading to open violence. Meanwhile, Selkirk and his associates became financially involved as they acquired one third of HBC shares prior to asking for a land grant in the Red River Valley for colonization.

The region was by then home to three different First Nations. In 1819 HBC employee Peter Fidler noted that Assiniboine people comprised the largest group in the region, mostly to the west of the Forks, with a population of over 7,500. He estimated that there were also about 1,260 Cree, from the north and the east, and about 800 Ojibwe, most recently arrived from the Great Lakes in the 1780s-1790s. These nations competed with each other, and with the Sioux nations to the south, in the fur trade, and for access to buffalo.

The region was also home to 181 “freemen” and their families, of mostly former fur-trade employees and their mixed-blood families. Specializing in the buffalo hunt and pemmican production, these people often came into conflict with the Assiniboine on the prairies. Generally linked to the North West Company, they developed a distinct cultural identity as Métis, with a widely used language, Michif, a mixture of French and Cree or Ojibwe.

When Selkirk brought his highland refugees to Red River, he introduced a destabilizing element into an already unstable and occasionally violent social situation. To flourish, or even to survive, the various groups inhabiting the region in 1812 formed competitive alliances. The hostility between the HBC and NWC drew the companies’ First Nations and freemen partners into a decade long struggle for commercial control of the Fur Trade. The initial 70 Selkirk settlers of 1812 found themselves dependent on those already established in the region and buffeted by events beyond their control.

Clearances in the Scottish Highlands. Until the 1750s, people in the Highlands of Scotland lived as small-scale farming tenants on the lands of clan chiefs. But by 1800, they were being evicted in favour of sheep. Thomas Douglas, fifth Earl of Selkirk, wanted to resettle these landless Highland Scots in North America. Using his personal fortune, he founded three colonies – one in Prince Edward Island, one in Ontario, and finally in 1812, the Selkirk Settlement at the Forks of the Red and the Assiniboine.

The grant of Assiniboia. Although western Canada was still almost entirely in the hands of First Nations people and Métis buffalo hunters, the area around the Forks was governed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) which had, in 1670, obtained from the King of England a grant of all the land drained by waters flowing into Hudson Bay. Believing that the Company was entitled to assign part of these lands to others, in the spring of 1811, Lord Selkirk obtained English title to a tract of some 116,000 square miles, to be called Assiniboia.

Gracious hosts. The land called Assiniboia on British legal documents was far from empty. Named for the Assiniboine (Stoney) people who had previously controlled access to the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, the area was, by 1811, also home to Ojibwe newcomers, Cree traders and Métis buffalo hunters. No one consulted any of them about the plan to bring settlers to the Forks. There were also a few permanent houses or cabins, the homes retired fur trade employees, known as “freemen”. These families supported themselves by hunting (especially buffalo) and some farming. Almost all of these families were Métis and had family ties with local first nations as well.

Competing Fur Trade companies. There were two forts at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine, on either sides of the Red River, one each for the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company. The “freemen” and Métis were generally affiliated with the North West Company (NWC) and the Saulteaux or Ojibwe and Cree were affiliated with the HBC although the situation was fluid and loyalties transient. The NWC saw the settlers’ arrival as an attempt by the HBC to interfere with their trade.

The Advance Party and their Wintering Camp on Nelson River. Under the command of Miles Macdonell, three ships and 105 men were sent to Hudson Bay with instructions for some of them to proceed overland to the Forks of the Red. They were to plant crops and build houses for the first of the settlers arriving the following year (1812). Macdonell and his men reached the HBC depot of York Factory in the fall of 1811, too late to proceed to Red River. The HBC traders at York Factory installed Macdonell and his men at a wintering camp a few miles up the Nelson River, and commissioned local First Nations people to provide meat for the group.

Miles Macdonell claims Assiniboia. Macdonell and the advance party finally reached the Forks late the next summer, on August 30, 1812. On September 4, Macdonell officially proclaimed his authority over the whole region as Governor of Assiniboia. Employing arcane Scottish legal terminology and contested English legal authority, he conducted a ceremony called “the Seizen of the Land”.

The first settlers arrive. A few weeks later, a party of about 70 settlers which had left Thurso, Scotland in June 1812, reached the Forks. It was late in October, as winter was starting to set in and they found the advance party unprepared for their arrival. The whole group walked south to Pembina, where Métis buffalo hunters supported and sheltered them for the winter. In the spring, the settlers returned to the Forks, and the first few houses were built, some ploughing was done, and some wheat was sown. A second party of (how many) settlers arrived in the fall but too little progress had been made for the settlement to sustain itself at the Forks. Everyone again trudged to Pembina, falling on the mercy of Métis buffalo hunters for a second winter.

The Pemmican Proclamation. The settlers’ presence stressed an already critical food shortage. Primed by aggressive competition between Fur Trade companies and provoked by the intemperate actions of the settler’s leader, Miles Macdonell, this crisis almost brought the Settlement to an end. In January 1814, Miles Macdonell ordered that no provisions, including pemmican, be exported out of Assiniboia. This act convinced Duncan Cameron, in charge of the NWC post at the Forks, who required pemmican (dried, pounded buffalo meat mixed with grease) for his canoe brigades, that Macdonell was trying to put them out of business. In 1815, Cameron commissioned Cuthbert Grant, a NWC clerk to organize a group of young Métis men to threaten the settlers and demand that they abandon the colony. Cameron meanwhile played a double game, offering to transport the settlers to safety in eastern Canada and find lands for them to settle there. More than half the settlers accepted this invitation. Miles Macdonell was taken to Canada with the others against his will.

Winter at Norway House. For the remaining settlers at the Forks, the danger from Grant and his men seemed so great that they abandoned the colony, retreating to Norway House at the north end of Lake Winnipeg. As they left, they were escorted by Ojibwe leader, Peguis, who had formed an alliance with the settlers. The NWC firebrands burned the settlers’ buildings and must have believed that the destruction of the colony was complete.

More settlers arrive. When agents of the Countess of Sutherland drove her tenant farmers from lands in the Helmsdale valley in the parish of Kildonan to make way for sheep, some (how many?) of these families made their way to the Red River settlement 1815. The (how many) colonists, new and old, settled down again at Red River for an uneasy winter.

The Battle of Seven Oaks. Food was still an issue. In July 1816, a pack-horse brigade carrying NWC pemmican, under the command of the insouciant Cuthbert Grant, tried to pass north of the Settlement. The Hudson’s Bay Governor, Robert Semple, with a party of armed HBC servants, stopped them at Seven Oaks. Grant’s brigade included well-armed buffalo hunters and skilled marksmen. Someone fired a shot, and within a few minutes a Métis teenager and 21 of the HBC men lay dead or dying. Cuthbert Grant later said that he would have gone to the settlers’ houses and killed “all he found there,” but for a second time Chief Peguis and his warriors intervened. Under Peguis’ supervision, the remaining colonists escaped and the bodies of the dead were buried in a single grave near Seven Oaks. Half of the settlers opted to go to Ontario escorted by the North West Company and the rest went to Norway House.

Lord Selkirk captures Fort William, and comes to Red River. The incident at Seven Oaks shocked Rupert’s Land. Lord Selkirk had already decided that a show of force was necessary to protect the colony. In the spring of 1816 he brought Swiss and French soldiers up the Great Lakes, captured the NWC depot at Fort William, wintered there, and proceeded to Red River in 1817, where he found the settlers just returned to the forks from Norway House.

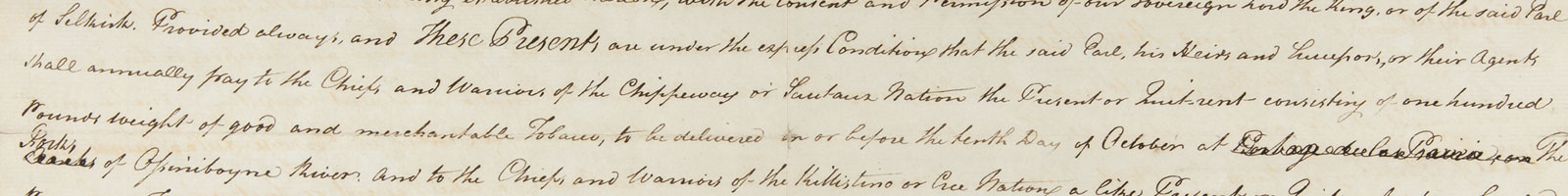

First Treaty. Here, on July 18, 1817, Selkirk signed an agreement with five Cree and Ojibwe leaders. Four Ojibwe and one Cree chief signed the Selkirk Treaty. Le Sonnant (Mache Whesab, Many Sitting Eagles), was a leader of the Cree, who had occupied the region for longer than the other signatories. The most powerful of the Ojibwe chiefs in the area was Le Premier (Oshki-doowad). As Le Premier’s power was fading, that of Peguis was rising due to his 1812 alliance with the settlers and the HBC. The other Ojibwe signatories were L’Homme Noir (Gaayyaazhiyeskibino’aa) and La Robe Noire (Makadewikonaye). When Peguis later recalled the Treaty signing, he noted that Le Sonnant did not offer any specific territory, but needed to be included in the Treaty due to his influence. Peguis himself offered the Forks area, Le Premier the Red River to Pembina, L’Homme Noir Pembina to Red Lake, and La Robe Noire the area extending to Portage la Prairie.

Although Selkirk, at least, regarded this as a formal transfer of lands which met the requirements established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 about the need to address the land rights of aboriginal inhabitants, Peguis treated it as an area for white settlers to establish farms which was to be shared. His band eventually took up farming land along the river within the area specified for settlers as did the Metis who settled in the area. The son of another signing chief, Black Robe, declared that the arrangement was understood that it was “simply a loan… the lands were never sold.”[1]. It was members of the Peguis Band who initially enforced the Treaty and kept the settlers within bounds. As time passed and power shifted, the Treaty ceased to be renewed annually as Peguis would have expected and the discussions about who controlled Rupert’s Land shifted to courts in England.

Starting over. After Lord Selkirk visited Red River in 1817, the remaining settlers rebuilt their homes and through succeeding winters became a successful part of a mixed economy, hunting and trading when necessary and tending to their farms and gardens when the weather was favourable and the crops were not destroyed by locusts or other natural disasters. They were protected for a while by Selkirk’s Swiss and French soldiers, many of whom eventually became settlers themselves. The settlers continued to depend on Lord Selkirk who paid for supplies from the HBC post at the Forks as did his estate after his death from tuberculosis in 1820.

Consolidation of Fur Trade Companies. The sometimes violent competition between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company lasted until 1821, and meant that things were unstable and anxious for all. When the companies merged and Hudson’s Bay Company took over sole control of the inland fur trade, the company assumed responsibility for local government, including religion, land tenure, and law and order. The amalgamation meant that many of the NWC and HBC clerks lost their jobs and they too moved to the Red River Settlement to augment the settler and freemen population and start new lives at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine.

The legacy of the Red River Settlement. In spite of great difficulties, the settlement showed that it was possible to establish an economically viable farm-based community in the climate of western Canada. The settlement was politically important as well, for without the British connections which were at the heart of the enterprise, the entire region might have quickly passed into the hands of the United States. Though they did succeed, at the time it must have been far from obvious that they would. We should not forget how hard it was for the first arrivals and how they depended on their Metis, First Nations and Fur Trade hosts for food and protection.

Two chiefs, Makadewikonaye, Le Robe Noire (left), and , Gaayyaazhiyeskibino’aa, L’Homme Noir, were important figures at Sault Ste. Marie when artist Paul Kane visited in 1845 and made watercolour paintings. In 1817, the chiefs had joined Peguis and his followers at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, where they signed the 1817 Selkirk Treaty. Their signs, the catfish and the sturgeon, indicate their clan affiliation.

BIOGRAPHICAL SECTIONS:

Cuthbert Grant. Cuthbert Grant was the son of a NWC partner and an indigenous mother. He was born at a fur trade post on the upper Assiniboine in 1793, and, after receiving a good education in Montreal including medical training, he was hired by the NWC as a clerk. In 1815 he was put in charge of the group of young Métis men sent by the NWC to terrify the Red River settlers; the confrontation with Robert Semple and the colonists at Seven Oaks in 1816 was the unhappy result. Grant himself was remembered by the settlers as a villain, but the rest of his career revealed an intelligent, responsible leader of the growing Métis community in southern Manitoba. He lived at the White Horse Plain, where the Catholic Church established a mission called St François Xavier. After the union of the HBC and the NWC, the HBC gave him the title Warden of the Plains and the responsibilities of a magistrate. Grant he led one of the major bison brigades based out of White Horse Plains and he later built a mill and used his medical knowledge to help his community. He was 61 years old when he passed away in 1854.

Peguis. He was also known as Cut Nose, Giishkijaan, was a leading Ojibwe hunter and trader and member of the Martin, Waabisheshi doodem, was one of the most influential Anishinaabe men in southern Manitoba during the first decade of the Settlement. His authority derived from his strategic relationships with the settlers and the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Anishinaabeg were a relatively minor presence in Assiniboia, newcomers to the prairie at a time when the environment was stressed by food needs of competing Fur Trade rivals Peguis became a “chief” in a rather accidental way (Quoting Fiddler here) but his friendship was important to the settlers whom he twice protected from NWC firebrands. In later years, Peguis accepted Christian baptism, though he did not abandon traditional practices. His baptized name, John King (King because of his political influence) led him to say, “now I am king, my sons will be princes”. Ojibwe people with the surname Prince, such as the war hero Tommy Prince, are descendants of Peguis. Having signed the land use Treaty with Lord Selkirk in 1817, Peguis understood the significance of formal Treaties with white authorities, and near the end of his life, he expressed concern that settlers were taking up lands that had not been covered by any agreement. He died in 1864. After Manitoba joined Confederation, Peguis’s son, Henry Prince or Mis-koo-ke-new (Red Eagle, Miskoginiw), was one of those who, in 1871, signed Treaty No. 1 with Canada.

————————————————————————————————

Text from the permanent We are All Treaty People exhibit at The Manitoba Museum:

WHAT IS A TREATY?

A TREATY IS AN AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONS

Starting in 1871, Manitoba First Nation’s leaders agreed to seven Treaties. Queen Victoria’s representatives obtained access to First Nations homelands in return for promises to provide for the well-being of First Nations people and communities. Canada’s obligations include the payment of annuities, the provision of education, allotment of reserves, and protection for the traditional economies of First Nations people. In return, Canada acquired the means to open up modern day Manitoba for settlement and agriculture.

A TREATY IS A COVENANT, A PROMISE MADE IN CEREMONY.

First Nations participants in the Treaty process acknowledged the binding nature of the Treaty with a pipe ceremony, creating a sacred commitment between nations meant to last “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the rivers flow.”

A TREATY IS A BINDING STATEMENT OF EXPECTATIONS AND OBLIGATIONS.

Canada acknowledged the binding nature of the Treaties with the signatures of officials on Treaty documents. They reinforced their obligations through the awarding of Treaty medals and gifts.

WHOSE LAND IS THIS?

The city of Winnipeg is built on land made available to Canada by Anishinaabe Chiefs in 1871 under the terms of Treaty No. 1. Prior to the 1800s, the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers were home to the Cree and the Assiniboine peoples. Winnipeg is also the homeland of the Métis. Métis political and economic control of our fledgling province was swept away in the aftermath of Canadian confederation. The ancestors of Manitoba’s First Nations people have lived here since the glaciers melted and the land became habitable. The first part of Manitoba to be settled was the high ground on the west side of Lake Winnipeg. Elsewhere in the Museum, one can see the 12,500 year old stone tools of Manitoba’s First Nations people. No matter how you look at it, First Nations people were here first.

A TREATY CREATES A PERMANENT, ONGOING RELATIONSHIP

We all benefit. We are all part of the Treaty legacy. The promises made in Treaties are made on behalf of Canadians. They are binding on all Canadians. Many promises made to First Nations people by Canada remain unfulfilled. If the intention was that First Nations peoples would be able to live economically and intellectually successful lives as equals citizens in Canada, with distinct languages and cultural traditions intact, then there are promises yet to keep.

PROMISES MADE

Hunting, fishing and trapping rights were guaranteed in the Treaties. The guns nearby are a reminder that First Nations and Métis people retained the right to hunt for those rights.

PROMISES BROKEN

First Nations and Métis people had to go to court to regain hunting rights.

PROMISES MADE

Canada agreed to protect Treaty lands on behalf of First Nations peoples. The pipes nearby are a reminder that this was a sacred promise.

PROMISES BROKEN

One of the worst instances of failing to protect Treaty lands in Canada was the 1907 forced surrender of St. Peters Reserve, a large tract of land north of Selkirk belonging to Manitoba’s Peguis First Nation. In 1998, after 91 years of argument and negotiation, the Government of Canada agreed that the surrender was illegal. In 2009, band members voted to accept a final payment of 118 million dollars in compensation. There are at least 20 outstanding land claims in Manitoba, and the settling of these claims may eventually include urban reservations.

PROMISES RENEWED

In 2005, Canada and the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs jointly created the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba. The purpose is to educate all Manitobans about the Treaties and to remind everyone of the strength of the long-term relationships formed by the Treaties. The current Treaty Commissioner is James Wilson. Dennis White Bird, former Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, was the founding modern Treaty Commissioner.